Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

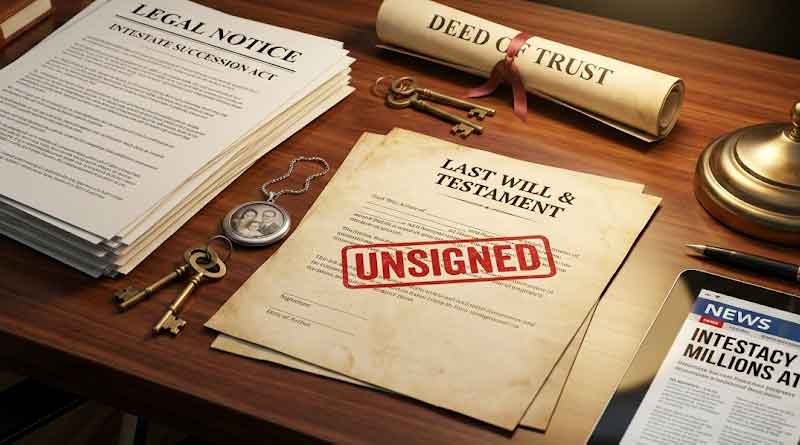

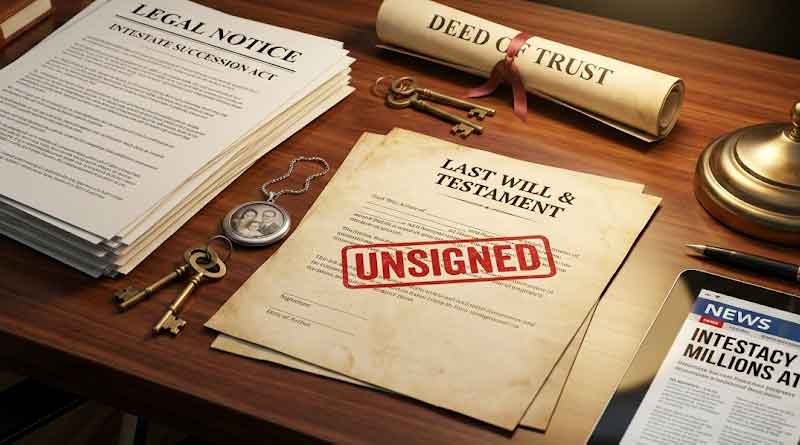

Intestate is the legal term for dying without a valid will, and it’s far more common than most people realize. When someone passes away intestate, they leave behind not just grief but a complex legal puzzle that state laws will solve according to rigid formulas—not according to what the deceased might have wanted or what families think is fair. This situation creates both informational and advisory challenges for surviving family members who must navigate probate court, establish legal heir status, and distribute assets while avoiding costly mistakes that could trigger disputes or personal liability.

The moment you discover a loved one died without a will, the clock starts ticking on decisions that will affect everyone who expected to inherit. Unlike estates with clear testamentary instructions, intestate estates follow statutory succession laws that vary by state and often surprise families with unexpected outcomes. Understanding this process isn’t just helpful—it’s essential for protecting your rights, honoring your loved one’s memory, and keeping family relationships intact during an already difficult time.

When someone dies intestate, state law immediately takes control through what’s called intestate succession. Think of it as a legal autopilot that distributes assets according to a predetermined hierarchy, regardless of the deceased person’s relationships, promises, or implied wishes during their lifetime.

The typical succession order follows this pattern: surviving spouse first, then children, followed by parents, siblings, and increasingly distant relatives. However, the actual distribution is far more nuanced than a simple ranked list. In community property states, a surviving spouse might receive only half the estate if there are children from a previous relationship. In common law states, the spouse might get one-third to one-half, with children splitting the remainder. These statutory formulas operate with mathematical precision but emotional blindness.

What catches most families off guard are the exclusions. Intestate succession laws typically don’t recognize unmarried domestic partners, no matter how long the relationship lasted. Stepchildren who were never legally adopted have no inheritance rights, even if the deceased raised them as their own. Close friends who provided years of care receive nothing. Charities the deceased supported throughout their life get bypassed entirely. The law recognizes blood, marriage, and adoption—period.

Blended families face particularly thorny situations. Many people assume “my spouse gets everything automatically,” but that’s a dangerous misconception. If you die intestate with children from a previous marriage, your current spouse will have to share the estate with those children, potentially creating conflict over the family home, retirement accounts, or business interests. This legal reality explains why even happily married people with simple family structures need wills.

Probate becomes almost unavoidable when handling an intestate estate, serving as the court-supervised process that legally transfers ownership from the deceased to their heirs. While some assets like jointly-owned property or accounts with designated beneficiaries bypass probate, most estates contain at least some property that requires court involvement.

The process begins when someone—usually a family member—files a petition with the probate court in the county where the deceased lived. This petition requests the court’s permission to administer the estate and formally asks the judge to appoint an administrator. Unlike estates with wills, where the deceased names an executor who carries out their written instructions, intestate estates leave this crucial appointment to the court’s discretion based on statutory priority lists.

The terminology matters here: executors serve estates with wills, while administrators serve intestate estates. Though their duties overlap significantly—gathering assets, paying debts, filing tax returns, distributing property—administrators face additional constraints. They often need court approval for actions an executor might handle independently, creating more paperwork, longer timelines, and higher legal costs.

Expect the probate process for an intestate estate to take anywhere from six months to two years, depending on the estate’s complexity, family cooperation, and court backlog. During this period, assets typically remain frozen, bills continue accumulating, and heirs wait anxiously for their inheritance while watching estate funds diminish through administrative expenses and attorney fees.

Courts don’t randomly select administrators—they follow priority lists established by state statute. The surviving spouse typically ranks first, followed by adult children, then parents, siblings, and other relatives in descending order of closeness. If multiple people share the same priority level (like several adult children), they can serve as co-administrators or agree among themselves who should take the role.

Being appointed administrator isn’t an honor or a reward—it’s accepting a fiduciary duty, which represents one of the highest standards of legal responsibility. As administrator, you’re legally obligated to act in the best interest of all heirs, even those you personally dislike. You must preserve estate assets, make prudent investment decisions, pay legitimate debts, and distribute property according to state law rather than your own preferences or family politics.

This fiduciary responsibility carries real teeth. Administrators who mismanage funds, show favoritism, or make reckless decisions face personal liability. If you sell estate property below market value to help out a relative, you might have to compensate the estate from your own pocket. If you distribute assets before paying all creditors, those creditors can sue you personally for the money they’re owed.

To protect against administrator misconduct, courts typically require posting a bond—essentially an insurance policy that compensates the estate if the administrator steals funds or makes negligent decisions. The bond premium comes from estate assets, adding another expense to the probate process. Some states waive this requirement in small estates or when all heirs agree in writing, but the default assumption is that oversight and insurance are necessary.

Proving family relationships seems straightforward until you encounter the complications that frequently arise in intestate estates. That estranged half-brother who never attended family gatherings has the same legal rights as siblings who stayed close. Children born outside marriage qualify as heirs once paternity is established. Adopted children have full inheritance rights, while stepchildren without formal adoption have none.

When someone claims heir status and others dispute it, courts hold heirship hearings to evaluate evidence. Birth certificates, marriage licenses, divorce decrees, adoption papers, and death certificates form the documentary foundation. But what happens when records are missing, were never created, or exist in foreign countries with different recordkeeping standards? DNA testing has become increasingly common for establishing biological relationships, particularly for children born outside marriage or in situations where paternity was never legally acknowledged.

Family disputes over intestate estates often stem not from greed but from divergent perceptions of fairness. One sibling provided years of caregiving while others stayed distant—shouldn’t that sacrifice be rewarded? The deceased promised certain items to specific people—don’t those verbal commitments matter? Unfortunately, intestate succession law ignores these considerations entirely, distributing assets by formula regardless of individual circumstances or moral arguments.

These emotional conflicts escalate quickly when money and property are at stake. Siblings who maintained cordial relations for decades suddenly stop speaking over disputes about furniture, jewelry, or sentimental items. The family home becomes a battleground when one heir wants to preserve it and another needs cash immediately. Without a will to provide clear direction, every decision becomes a negotiation, every negotiation risks becoming a fight, and every fight potentially requires court intervention.

Real estate creates some of the most challenging situations in intestate estates. Unlike bank accounts that can be divided precisely, houses and land are indivisible assets that become fractionally owned by multiple heirs. When three siblings inherit their parents’ home equally, they face difficult choices: sell it and split the proceeds, let one buy out the others, or retain joint ownership with all its complications.

These decisions grow more contentious when heirs have conflicting financial situations and emotional attachments. One sibling might desperately need their inheritance to pay medical bills, while another wants to preserve the childhood home and has the financial stability to wait. One might be ready to accept the first offer, while another insists on holding out for top dollar in a slow market. Courts can order partition sales when heirs deadlock, forcing the property to auction even if everyone prefers avoiding that outcome.

Creditor priority operates according to strict legal hierarchies that administrators must follow. Funeral expenses typically come first, followed by estate administration costs, taxes, and then general creditors. Only after satisfying all these obligations can heirs receive distributions. This priority system sometimes means heirs inherit nothing if the estate is underwater financially—creditors get paid while the family receives only headaches.

Administrators must actively identify all debts, not just wait for creditors to come forward. This requires reviewing financial records, tax returns, credit reports, and correspondence. Missing a legitimate debt can create personal liability, while paying questionable claims wastes estate assets that belong to heirs. Determining which claims are valid, negotiating settlements, and sometimes litigating disputes become significant parts of the administrator’s burden.

The “wait and see” approach to intestate estates multiplies every problem. Assets depreciate, opportunities disappear, and conflicts intensify as time passes without formal structure. What seems like avoiding hassle actually creates bigger hassles down the road—frozen bank accounts, inability to access safety deposit boxes, property falling into disrepair, and family members making contradictory claims about who promised what to whom.

Early consultation with an estate litigation or probate attorney provides clarity when emotions run high and information feels overwhelming. These professionals understand your state’s specific intestacy laws, can explain realistic timelines and costs, and help families avoid the predictable pitfalls that turn manageable estates into years-long nightmares. The attorney fees spent upfront typically save multiples of their cost by preventing mistakes that trigger litigation, personal liability, or family rifts.

Regional variations in probate law matter tremendously. Community property states handle spousal inheritance differently than common law states. Some states exempt small estates from formal probate, while others require court supervision regardless of estate size. Filing deadlines, bond requirements, creditor notice periods, and distribution procedures vary significantly across jurisdictions. Generic internet advice about intestate estates might not apply to your situation—local expertise makes the difference between efficient administration and costly errors.

Professional assessment of the estate should happen immediately, not eventually. Schedule consultations with probate attorneys, gather financial documents, inventory assets, and begin understanding the scope of what lies ahead. This upfront investment of time and money pays dividends throughout the administration process, protecting both your interests as an heir and your responsibilities if appointed administrator. When someone dies intestate, the only thing worse than dealing with the legal complexity is dealing with it after preventable problems have already occurred.

The death of a loved one never comes at a convenient time, and discovering they died intestate adds legal confusion to emotional grief. But with clear information, professional guidance, and understanding of the stakes involved, families can navigate intestate succession successfully. The key is recognizing that state law now controls the outcome, that time matters, and that the decisions made in the weeks following death will affect family relationships and financial security for years to come.